Man, it really feels like spring. Shoutout to all my transitional season lovers out there, we finally got a real one this year it seems. The bike tires have been pumped up, the sun is out, I’m getting randomly asked out while chilling in the park, can’t complain about the vibes to be honest. Got a stacked Dispatch this time around, a brief art history lesson, a dissection of Creativity as Commerce through social media and what I’ve taken to calling “Maker”-core. Also, some reccs for things I’ve been enjoying recently as the weather gets nicer. Finally, a cult classic favorite product is coming back better than ever, and to celebrate the arrival of bike season, I put together a little playlist to get you hyped. Thanks for the continued support on the newsletters, as this goes on I want to eventually do more and more with it, and the feedback has been nothing but vindicating. As usual, thank you for reading.

-ms

Table of Contents

“Attention Economics”

Recent Pieces

“Bring the Bikes Out” - a ride playlist

5 Things I Actually Like

Refer my newsletter to some friends to unlock a few months for free and remove the paywalls on every edition, PLUS get access to the full archive!

⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘

A Word From Our Sponsor

Bike jerseys are back baby. New colorway and the original Amor Fati version return later this month. Stay tuned…

⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘

We are in the midst of our second decade of social media dominating and setting the standards for ways one might live, and as a result of this drawn out adjustment, new standards for things have gradually mutated to match the changes as they occur. In order to properly keep up with the new information superhighway, those that wish to utilize it as a tool have to be reactive to it in real time. At this point in the online experience, nearly every mainstream form of communication has become dictated by the respective platform it exists on (Different algorithmic rules to abide by on Instagram versus Twitter versus Tiktok). Those platforms are removed from our control, and liable to rapidly deteriorate or flourish at a moment’s notice. More than ever, it feels like we are subject to them if we wish to use them for any of our own purposes, rather than feeling a part of them. Constantly adjusting or adapting to an ever-mercurial digital sea. There’s maybe no better example of this (or rather no one I’m more qualified to talk about) than the warped relationship between artists, designers, creatives, and social media.

In its halcyon days, the landscape of, and in turn how we used, social media felt entirely different. More like a supplement to the things in real life for artists of all kinds. An ethereal, more ephemeral space to post recap pictures of a gallery opening, or tour dates, or glamour shots of a product on display. Eventually by the mid 2010s however, the platform itself became the gallery space, the showroom, the auction house. I witnessed this change occur in real time from the front lines. When I first began posting my work on social media, it was almost unheard of to anyone I talked to. No matter how thoroughly I tried to explain to them what I knew to be possible, they couldn’t seem to comprehend it. Now, the idea of not having work on social media is seen as preposterous. From arguments with professors about the necessity of posting portfolios to these sites, of exploring that (at the time) seemingly untapped oil field, to watching hundreds of derricks constructed what felt like overnight. Social media quickly became seen not just as a valid space for one’s work, but the explicit, sometimes only intended destination for it. Compounded only further by the 2020 pandemic, which saw nearly everyone occupying the digital world and finding new things through it, a massive switch was flipped, and an entire sub-economy was cemented.

This sub-economy, much like its IRL counterpart, is subject to ebbs and flows, highs and lows. Subsequently, again like the in-person version, a sort of virtual stock market arose from this new digital hierarchy. Very quickly, the easy quantification of likes, followers, views, etc allowed for new type of supposedly calculable value to be formed. One of attention. Eyes on at any given moment. A synthetic symbol of what a thing (product, piece of art, thought) is worth. Over time, through this now industrialized system, the focus began to shift, with that synthetic worth becoming the new goal. Things made explicitly for social media, or to appease the algorithm, or microtrends, or in reference to something that happened recently in the new public consciousness of the TL. The idea of the digital space being strictly for the runoff of the real world vanished. In terms of art and creation, now more than ever things are created expressly with an abstract audience, or more specifically this market (both possesing a potentially infinite amount of attention), in mind. Gradually over enough time (around a decade with an extreme bump 5 years in), the market, its dominance, and its allure, will begin to influence not just the thoughts surrounding the commodities being pushed, but the commodities themselves from their creation.

Zombie Formalism

A perfect example of markets beginning to dictate the work, one that we are still seeing the lingering effects of today, can be found around the same time as the rise of social media 15 years ago in the art world. I think in order to properly understand the state of commodified creativity we find ourselves in now, it’s important to look back at this time and see what I believe laid the groundwork. Zombie Formalism is the name attributed by critic Walter Robinson to a movement of (mostly) derivative abstract contemporary art that emerged in the early 2010s coming out of the 2008 recession. After the economic lows of the late 2000s, the art market was oddly enough the first thing to “bounce back”. This was primarily because after the turmoil and instability of traditional economic assets the last few years, wealthy traders turned to more abstract “alternative” assets like fine art, as the value of a painting or sculpture isn’t necessarily tied to the state of the economy or high material overheads. This is the first key to keep in mind moving forward: In times of recession or economic lows, art is treated as an investment, a commodity, a stock alternative.

Quickly, as art trended as a cushioned investment strategy among the elite, Wall Street traders began to label themselves and be seen as “collectors”, or “patrons of the arts”. Although the terminology changed, the tactics were still the same. It was still seen as just trading assets. With a world as subjective as art, investors realized that they could manipulate the market in ways that were beyond banned from the typical financial realm. In what would now be recognized as essentially pump and dump schemes, many of these rich, powerful traders would find young rising artists making tastefully inoffensive, easy to display, unmistakably vague abstract art, buy the pieces for around 5 figures, inflating the cult of personality around the artist via social media and word of mouth, then once the artist or work was notorious enough, flipping the pieces at auction for oftentimes a 10x profit after a few months. The painting never changed, the artist was still alive, but the value inflated, almost entirely artificially. We still see this strategy being used to this day, in the last few years with NFTs (lmao) and now with detritus meme coins. The issue with this was that these “collectors” and a lot of the pieces they sought out were entirely removed from the vein or context of art history. Paintings weren’t purchased because of their intrinsic artistic merit, but rather with their agreeability, their ability to look nice as decoration in a penthouse living room (oftentimes several through the multiple owners), and most crucially, how they looked online.

Because the budding social media platforms, mainly IG, were the main tool used by these collectors to boost an artists “stock price”, safe abstract art that photographed nicely became the top commodity. The new market wanted art inherently made to be shared online, so of course, that began to dictate the art that was made. Artists started to make works directly with that new market in mind. Bland, usually very derivative (recalling more exciting midcentury abstract artists like Rothko or Pollock) pieces that focused more on the sellable story of making the work rather than pushing any type of boundary or a statement that could potentially turn any investors off. Often, the spectacle of the process of making a painting was put on the forefront of the pitch to potential collectors as a way to “justify” it, or put the emphasis on the vague concept of Creativity as a whole rather than something more pointed and distinct. Characteristically, the pieces were large in size, hyper contemporary, distinctly abstract, and utilized unorthodox ways of rendering that became part of the synthesized story of the work. Theatrics and spectacle became encouraged to prove the creativity of the artist. One of the more famous examples was Lucien Smith’s Rain Paintings, which saw empty fire extinguishers filled with paint and sprayed in order to recreate the look of raindrops on the canvas, a showy move we still see variations of to this day. The process of a work’s creation became not so much a part of the work itself but more so folded into the mythology or market value of the artist. This set a new standard for how contemporary art was thought about by those collectors, divorced from art history and theory, and is also the next key to keep in mind: The spectacle of Creativity or process of making art can be just as commodified and “sold off” as the piece itself, and can be dictated just as much by the market.

I wanted more than just my personal take on this period for this essay, so I reached out to friend of the Dispatch Andrew Kuo, a fantastic artist himself and co-host of personal favorite basketball podcast Cookies to get some of his thoughts on the impacts of Zombie Formalism. He describes it as “a traditional call-and-response between artists and the market, not unlike figuration after it, but it coincided with a time of economic health that made people pause at the volume of paintings and speculative sales…I don’t think Zombie Formalism was the true blueprint as much as Zombie Collection/Curation, which is still going on in the margins.”

As we’ve seen, investors, corporations, and other financial whales, these Zombie Collectors without art historical context can make (supposed) waves and have an impact on not just the market of certain types of art, but the art being produced itself. Once the word got out that this type of bland, safe abstract art with an emphasis on quirky processes was making big bucks with reliable “patrons”, a slew of artists followed suit trying to cash in for themselves. The only problem? Once the investors had their “portfolios” filled, and the paintings had been passed around that small subsection of collectors like an Eastern European model, a glut of extra works remained, with the only potential audience being the more discerning, more acutely trained eyes of real enthusiasts, who did not want any part of the paintings. Around 2015, the floor of Zombie Formalism seemed to drop out overnight, with many of the finance bros turned collectors suddenly scrambling and furious that they couldn’t flip and unload their stash of contemporary decorations. However, despite this crash, it’s hard to say that ideas of the movement really went away. Coincidentally, the rise of the Zombie Formalism “Everything can be flipped” mentality lined up right alongside the mainstream introduction of things like clothing reselling and commodified Hype in streetwear, which we see applied to any and everything now from Stanley water bottles to Trader Joes tote bags. Finance chuds have found their new pseudo-artistic pump and dump ventures in the forms of NFTs, generative AI, and various crypto grifts, and I might be inclined to say that might be for the best. Only people with the type of taste that those things appeal to deal with those worlds, but it appears that the average person’s taste is rapidly reaching those levels as well.

Kuo remains seemingly hopeful on the matter though, “Flippers will always flip, but I [think] the transfer of intellectual wealth is happening, and the future of the art vs art market world will be controlled by people we may or may not agree with? The flattening of high/low will def provide us with interesting art and new ways to do business around it. I hope I’m not too grouchy to enjoy it.”

There has absolutely been a surge in democratization when it comes to art in the last decade, thanks in part to the continued use of social media, now being used by artists directly through DTC. I myself have directly benefitted from this shift. There was definitely a level of agency over ones own work that was given, especially compared to the cutthroat gallery scene or connection based retail buyers of previous eras. However, as we’ve seen, even with other aspects of social media, a larger scale platform or audience, now a direct, lightning fast one, is still extremely impactful on the things that wind up reaching it. Even beginning to dictate the work, the story of it, and how it’s presented in its own way, just like any other market. Through the rise of the artist as a Personal Brand, the multi-hyphenate creator era of social media, I would argue that now, those core values of Zombie Formalism and its collectors have mutated into something much more ubiquitous. The long arms of auto-mythologizing, theatrics, exploitation, and more still stretch deep into the 2020s and have even become the new standard.

“Maker”-core

Fast forward to now, the post-pandemic extremely online gig economy we find ourselves in, and we can see that the ideas of Zombie Formalism essentially laid the foundation for how nearly all online artists and “artists” approach social media. People have become both the painters and the art dealers at once, simultaneously tailoring their work to fit the market presented to them while attempting to boost their own notoriety or spin their own lore to jack up their theoretical stock price. Synthesizing prestige, or merit, or dare I say aura in order to inflate one’s own perceived value. However, the artifice of the entire process, the hollow plastic of the façades being built still shines through the screens, getting too impossible to ignore.

The general public’s own attitudes toward and consumption of art has drastically mutated in the time since the mid 2010s. For most people now, their primary consumption of art of any kind is either through or tangential to social media. Simultaneously, that same lack of historical context, lack of art literacy, and lack of appreciation for theory that defined the Zombie Collectors is now how the average consumer navigates the more democratized online art space. Now that these attitudes are on a much, much bigger platform or market, it has led to an even greater mutation of things that are made specifically for it, be it art, opinions, ideas, or anything else that can be commodified. Think of a “Tiktok designer”, a “Twitter illustrator”, an “IG brand”, and solid archetypes of each can immediately clearly appear in your head. The ethereal but drone-like online markets have begun to dictate the creation fully, and as a result we are left with in my opinion more and more homogenized, ambiguous, (zombified maybe?) aesthetics. There is an entirely modern form of artist self-commodification going on that more directly reflects the Freelancer driven gig-economy of today while still carrying the values of Zombie Formalism before it. Something I’ve taken to calling “Maker”-core.

“Maker”-core can roughly be defined as a consequence of a decade straight synthesizing the online Creative as a catchall archetype. A bland, malleable, often quirky, corporate friendly entity that is to online artists what Zombie Formalism was to abstract painting. In the age of the multi-hyphenate, the idea of creativity itself has become the commodified, tradable asset, and mirrors the Zombie Formalist movement in more ways than one. First, we can look at the way the act of making something has once again been exploited for this market value. The rise of the “Watch me make a ___” Tiktok video or the sharing of process pictures to boost a post on Twitter have once again turned the studio into spectacle, something that needs to be beautified to be consumed alongside the final product. Much like the Zombie Formalist emphasis put on the methods of making a piece of art to boost the notoriety or lore of the artist, “Maker”-core commodifies the journey, the most internal part of creation, in order to sell it off to the public as a wholesale product. In turn, the act or process of creation itself begins to be dictated and directed by the online attention market. “Here’s how I made this!” starts to feel less like a glimpse into the process and more like a straight up sales pitch. Now that the sheer amount of consumption of art and information is at an all time high through social media, and now that the delivery method for those things (via posts) are so fleeting and ephemeral, the reaction to that has been to simply add more into what the commodity is. It’s no longer enough to simply share the tangible end product, lest it end up in the screenshot abyss, it now has to be paired with the more abstract supplemental process in order to bulk up the perceived value. I can’t tell you how many people have suggested to me that I make short videos detailing the “behind-the-scenes” of making my jewelry or ads or anything else, and I give the same answer every time: my process is not pretty, and in my opinion, it doesn’t have to be. Creation of any kind is an extremely personal, intimate act. Sometimes it’s hectic, nasty, ugly, tumultuous, agonizing, all things that are inherently against the aesthetically smooth process pictures and videos of modern social media artists. Oftentimes, now and throughout most of art history, there is a reason that the public only sees the end product. The delicate nature of the relationship between presenter and viewer. Once the threshold into the public has been crossed, I believe you relinquish some of that intimacy to your work. Additionally, there is no limit for what can be commodified under the modern self-exploitation brand building of social media. How much process do you need to share to justify a piece of art existing? Are some processes more inherently valuable? Having to create, and having to make the undertaking of it presentable for an audience not only doubles the amount of panoptic, voyeuristic labor done by the artist, it completely throws off the personal relationship between them and their work, transforming it all into simply just another product, just Content.

The other main side of “Maker”-core is the idea of the Creative as a blanket archetype used by people and now especially corporations to further homogenize the act of creativity. There is an entire online ecosystem of art about making art, design about designing, and so on. The spectres of Zombie Collector mentality still haunt us. Artistry and creativity are treated as decoration instead of an active practice, almost like a logo to be cheaply brandished. Speaking from personal experience, many brands and corporations aren’t looking to actually be artistically daring or forward thinking, but rather want the appearance of being “tapped in”, or having a façade of creativity. Similar to the financially minded Zombie Formalist “collectors” of the past, they assemble a roster of “Makers” at an arms reach in an attempt to benefit from association without actually dedicating anything to the cause of art (beyond money of course). Again, it has nothing to do with the actual quality of the work itself, but more the symbol that it represents, what it’s presented as. People still go for it though, again like before in the days of Zombie Formalism, because it is really, really hard out here, and that monetary temptation will always be a factor. Like before, theatrics and spectacle become encouraged in order to try and lasso one of these hulking cash cows. Quirky stunt projects, products, and processes meant solely to draw Attention Value.

There are many different proponents of this, but I don’t think there’s a more concise embodiment of “Maker”-core than MSCHF, the startup famous for the big red boots and other “we get it” stunt products. A pretty one-note “marketing experiment” turned VC funded juggernaut of an entity, the brand and its wave of derivatives perfectly encapsulate Creativity as a homogenous commodity, a lame decoration. Another example could be Gallery Dept, and its brand of insane markups for Levi’s splattered with paint (we’ll ignore the margiela rip off for the sake of time) and its vague platitudes about “artistry” as an attempt to justify them. These brands’ popularity (and same manufactured reactions to their stunts every time) display a population that has taken the values of those Zombie Collectors and made them the norm, one that is comfortable with never analyzing further than surface reactions to art, one that prioritizes Creativity and quirkiness solely as a commodity or logo. Even at the time of writing this, Nike has announced their latest foray into "“internet culture” with their own quirked out stunt product in the form of (frankly fucking embarrassing) pre-cooked AF1s. A product in particular that feels like maybe a death rattle or breaking point for this whole style of milquetoast diet irony half-shrug product. “Silence, brand”: the shoe. I’m frankly exhausted by everyone trying to be le epic troll and being so bad at it. The issue isn’t that I’m annoyed or mad, it’s that I’m bored. It feels like this is all we’re left with now for a majority of outputs, the final form of “well, all press is good press 🤓”. The Long 2017 continues onward, hoarse throated and deteriorating from years of untreated irony poisoning, cognitively declining into a mess of nothing symbols and vaguely referential hand waving gestures. It’s hard for people to fathom any enjoyment from deeper analysis or theory now, so the value comes purely from the cheap spectacle, the vague flavor of artistic inclination like a bland La Croix. The commitment to “The Bit”, the vague and hollow meta-”commentary”, the familiar thing repackaged in a different box that makes it feel new this week compared to last. A plastic Creativity slurry made solely for social media under the guise of a shallow “statement”, the product design version of those lifeless abstract paintings appearing in millionaires’ IG pages over a decade ago. At this point, we may not only be irony poisoned, we may also be quirk poisoned.

Where Do We Go From Here?

I guess the point of all this is to say we should be thinking about artistry and creativity as what they are: labor. Yes, it’s a dream to do what you love for work, but it still should be thought of as work. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing either, the labor of one’s creative process is where the deep connection to the piece comes from, the fulfillment through working with your hands and mind. It can be a beautiful, transformative, intimate process. Whether it’s a song, a ring, a movie, a painting, or any other form of expression, the work that goes into it is what leaves it covered in invisible fingerprints, the texture of hours of human life and energy instilled into this finished product. Marxist theory regards Labour Power as both the labor itself, and the symbolic commodity of it that gets stripped away from the laborer when it’s sold off to or exploited by someone else. It’s an easy concept to grasp when using examples of things like factory work, which is a direct, nearly quantifiable physical labor traded off for money, but what about in the ethereal world of creative labor? What about a world where you are your own exploiter, where it’s normal practice to sell off as much of yourself as you possibly can to everyone in hopes of further “climbing the ladder”?

Every job is dictated by some type of market, but when that market is seemingly endless, vaguely defined with almost no structure, changing at a moment’s notice, it’s not surprising that people wind up exploiting themselves, because it seems to be the only way presented to us right now. Yes, these collectors or companies trying to be cool may provide money or (alleged) prestige in exchange for our labor, but is that really the fulfillment, the freedom we’re looking for? Unfortunately, I don’t have all the answers. If I did, I probably wouldn’t still be on social media myself at this point. Regardless, if there are lessons to be taken from Zombie Formalism and our current era of “Maker”-core, I believe they are about being conscious of one’s relationship to their work, their agency in controlling what they do or do not relinquish and pawn off to the highest bidder. What we choose to keep to ourselves, for ourselves. When we commodify even the personal past labor of our processes of creation, are we “getting what we’re owed” for it, or really stealing fulfillment from ourselves?

⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘

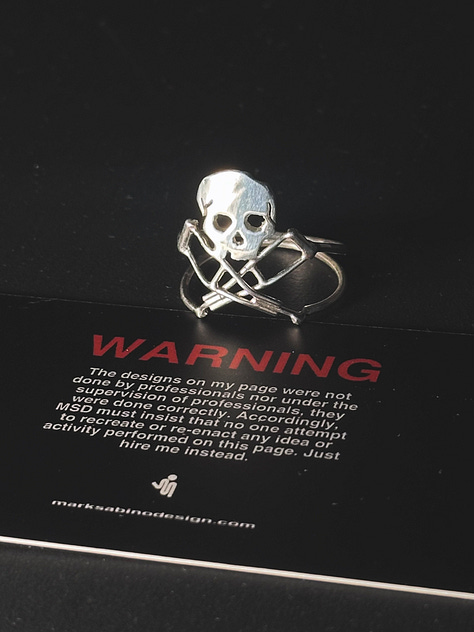

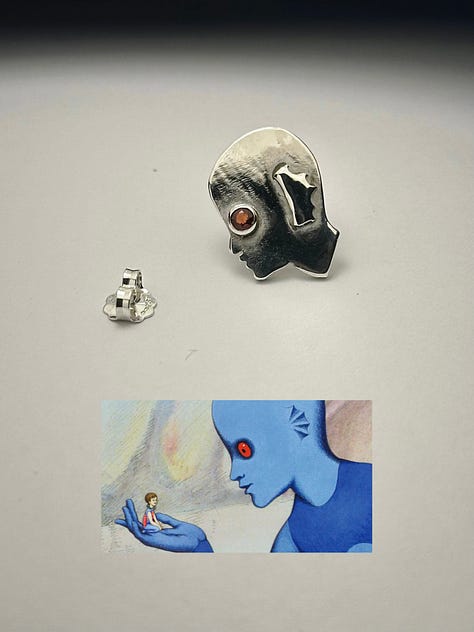

Recent Pieces/Mockups

Discounts still going strong, available at hello@marksabinodesign.com

⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘

Apple Music

⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘⫘

The Comedy (2012)

Now free to watch on Tubi, Rick Alverson’s searing look at a very specific brand of millennial malaise starring Tim Heidecker, Eric Wareheim, and James Murphy (of LCD Soundsystem) is surreal to watch in 2025. At the time of its release, this portrait of rich, apathetic, middle aged Brooklyn hipsterism during the waning years of the Williamsburg boom might have been seen as snide cynicism or exaggerated nose-thumbing to some, but looking back on this frighteningly vivid time capsule now, it comes across entirely differently. This movie serves as a perfect snapshot trapped in amber of the attitudes that led us to our current moment in time in New York and America, maybe even crafting a crystal ball vision of what might await us in the future if these ways of operating aren’t adjusted ASAP. Heidecker plays the main character Swanson, who represents a sort of irony-poisoned greek myth, being entirely removed from any perceivable sincerity for nearly the entire runtime. A rude, selfish, brazenly offensive and unfunny man, it’s very rare that you encounter a movie that offers so much potential contempt for its subject(s). At the time, this protagonist may have felt like a blown out hyperbolic caricature, and to some extent it still is, but in 2025 these repugnant, sincerity-deficient types of people are much more the norm, oftentimes being rewarded or celebrated for it. This gives the entire film a new context in our modern day. It feels like a warning, a signal flare that was shot out a decade too early, trying to show the dangers of a fully ironic, detached existence. The only logical endpoint of a generation of self-described “scumbag” aesthetics and perpetual adolescence that gives way to a hollow adulthood without substance. Despite the name, this is a truly desolate feeling movie. Some of the scenes are genuinely still tough to sit through without squirming in discomfort because they feel terrifyingly, excruciatingly plucked right out of real life. Its almost as if they perfectly captured and distilled the exact dissociative feeling of the smile leaving your face on a shitty drunken night in an apartment you’d rather just leave and turned it into several vignettes. The real angst or despair of watching this movie in 2025 isn’t the outrageousness of the actions of the characters, but the sinking realization that these people are the end point from which we are all only a few steps away without sincerity in our lives. If there was any doubt about the thesis of the film, one scene in particular that perfectly utilizes William Basinski’s haunting The Disintegration Loops (A piece of music I wrote about extensively here) dispels them fully, creating a foreboding feeling of hopelessness to contrast the detached fun being shown. A nastily accurate encapsulation of a very specific era that serves as both an illustration of how we got to where we’re at now, and where our own rising detached, ironic personas we have become accustomed to could be leading us. An existential must watch.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Guy Not A Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.